Description

The description of the axe beak in the original 1977 Monster Manual is, as is true for most creatures in this book, quite terse and we are basically only told that these flightless birds are fast runners that aggressively hunt during the day. The stat block shows that they are encountered in small groups of 1 to 6 animals.

|

| Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 1st edition Axe Beak. |

In the AD&D 2nd edition book Monstrous Compendium Forgotten Realms Appendix from 1989 the axe beak gets its first lengthier description and while they are still described as flightless, carnivorous birds that appear in small groups of up to six animals, it is now also stated that they are four feet tall at the shoulder, and that their legs resemble those of an ostrich. We also get an in-depth description of how their loud honking voice can be heard for half a mile, that the males make a drumming sound like a bass violin during mating, and that the birds hiss during combat.

Furthermore, we are told that the axe beaks make crude nests of stones atop rocky outcroppings and that hatchlings can be raised as guards, hunters and mounts. This is the first mention of the fact that the axe beak can be tamed and used as a mount. This fact also explains that the axe beak eggs are worth 50 gold pieces and that the hatchlings are worth 80 gold pieces. It is also mentioned that the long plume feathers of the wings and tail are worth 2 gold pieces each, but we are not told what exactly they can be used for.

|

| Axe beak in the AD&D 2nd edition Monstrous Compendium Forgotten Realms Appendix from 1989. |

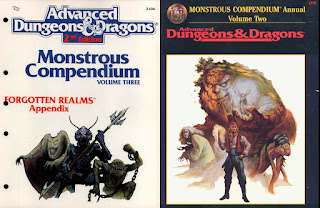

The Monstrous Compendium Annual Volume Two in 1995 was part of the revised version of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd edition ruleset (the release with new front pages that matched the Players Options books) and this book kept the stats and description from 1989 unchanged, but with a new image added.

|

| The new image of the Axe Beak from the Monstrous Compendium Annual Volume Two in 1995. |

In the Arms and Equipment Guide that was published in 2003 for the 3rd edition Dungeons & Dragons, the axe beaks are described as omnivorous, and for the first time, the beak is both depicted and described as having a prominent axe shape that can be used as a weapon. Before this the name seems to have been more symbolic, indicating an animal with a dangerous beak. The text in this book also adds the peculiarity that axe beaks are attracted to shiny objects such as jewellery or polished metal, to the degree that people would refrain from polishing their armour if they planned to use them as mounts.

The axe beaks in this version are the fastest they have ever been. Their base movement speed is higher than for any horse, but in addition, they also run five times their normal movement speed, while horses only run four times their normal speed. They also have keen eyesight, but only in daylight.

Another new feature in 3rd edition is that the axe beaks can be trained as adults. In the AD&D 2nd edition version they had to be trained from they were hatchlings, but now a Handle Animal check (with DC 18) is enough to turn them into mounts. It is however still much easier to train the young ones (DC 11).

Finally, the stat block reveals that the axe beaks live, or at least move around, in larger flocks of 5 to 20 animals.

|

| Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition Axe Beak with its prominent beak in 2003. |

In its latest version of the Dungeons & Dragons 5th edition Monster Manual from 2014 the description of the axe beak is again very short and without an illustration. The animal is described as a flightless bird with strong legs that has a "…nasty disposition and tends to attack any unfamiliar creature that wanders too close."

To find a recent official illustration of the axe beak, we have to go to the supplement Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden from 2020. In this book, the animal is presented as a potential mount and here it seems as if the birds are also commonly found in cold climates: "An axe beak's splayed toes allow it to run across snow, and it can carry as much weight as a mule". It is of course possible that this is a different, but closely related species to the standard axe beak that has adapted to cold climate in the same manner as polar bears. The depiction does look quite different from the earlier images of the animal, showing a bird with predominantly white feathers covering most of its legs. It is also evident from the text that adult domesticated axe beaks are common enough to be purchased for 50 gold pieces, which is actually cheaper than a normal riding horse.

|

| Axe beak from Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden published in 2020. |

Inspiration

The axe beak was obviously inspired by real flightless birds. Already in its first appearance in the 1977 Monster Manual, the ostrich is mentioned as a comparison, but it is also likely that inspiration came from the various species of now-extinct carnivorous Phorusrhacidae, also known as terror birds. The different species of these giants could be up to 3 meters tall and were in periods most likely apex predators, at least in South America, until they eventually became extinct between 100 000 and 20 000 years ago.

One famous example of such a bird is the Titanis walleri, from which fossils have been found in present-day Florida, Texas and California. The first finds of this species were made in the 1960s and these discoveries would still be new and interesting when the axe beak was first envisioned a few years later.

|

| Reconstruction of Titanis walleri (image by Dmitry Bogdanov). |

Behaviour

The description of the axe beak varies somewhat over the years, but a few things remain constant. They are always described as aggressive, fast-moving flightless birds that eat meat (but maybe not only that), hunt during the day and live in small flocks.

In later versions the focus shifted somewhat towards the possibility for the axe beaks to be domesticated and used as mounts. The different published versions of the animal have given us several interesting details and behaviours that can be used or ignored as one sees fit.

How to Use the Axe Beak in Practice

While being aggressive and dangerous, the axe beak does not have to be just another monster. They can definitely be used as a threat, especially if they attack in numbers and in a somewhat organised manner, but they are not only that. Axe beaks are unaligned and in no way inherently evil, and they can be used as both colourful background elements, a source of food and, maybe most interestingly, as companions and mounts.

From the 2nd edition AD&D in 1989 and onwards axe beaks have been described as potential mounts and companions for hunting and guarding. In that version, they had to be reared from they were hatchlings, while 3rd edition opened up for domesticating them as adults. I think that it should be possible to tame an adult axe beak, as you could with a wild horse, but it should also be a difficult and dangerous task. As with most things in life, the danger and difficulty will make success even sweeter for the character that attempts this.

The 5th Edition Axe Beak

The 5th edition version of the axe beak is if you look at the stats unfortunately slightly underwhelming as a mount. Compared to an ordinary riding horse the axe beak is slower (50 feet movement compared to 60 feet for the horse), and has lower Strength as well as slightly lower Wisdom and Charisma. It has a bit higher Dexterity, but that is of little use since its attack is Strength-based. For some reason, the horse's hooves attack also delivers more damage on average than the bird's beak, and the higher Strength of the horse makes these attacks both more likely to hit and to deliver more damage. In earlier versions as a comparison, the axe beak was at least as fast as a horse and sometimes (as in 3rd edition) much faster.

If someone wanted to house-rule the axe beak to be a bit more formidable like it used to be, one way could be to increase its movement speed to 60 feet and maybe also increase the base damage of its beak attack to 2d6. This would give the attack the same damage as the claws of a brown bear. Alternatively, the axe beak could get Multiattack with two beak attacks per round, or even one attack with the beak and two with its claws, as it used to have in earlier versions. In the latter case, the claws should probably inflict relatively little damage, for example, 1d3 slashing for each attack.

Another thing that could be considered is to give the axe beak a special rule that it sometimes can be unpredictable and aggressive as a mount. Normally any controlled mount in 5th edition can only use the actions: Dash, Disengage, and Dodge, but an aggressive hunter such as an axe beak could have Attack as a fourth option. To balance this you can add an Unruly trait that is triggered if the creature has recently been injured and a creature that is not the rider or another axe beak comes within 5 feet of it. In such a situation the rider has to make a Wisdom (Animal Handling) check with DC 15 to prevent it from attacking.

If you are interested in seeing a modified version of the axe beak for 5th edition, or a version of this classic creature adapted to Free League's Dragonbane RPG, you should take a look at this earlier post: